Well, I’m not quite sure about that, because I was still learning and putting it together. I was halfway through the tree. In other words, I started out with a big tree and I tried shaving and shaving and shaving try to find the perfect toothpick, but I wasn’t there in 1960 — definitely. I was nowhere near the toothpick at that moment.This is a startling and original metaphor for an artist trying to find his or her own voice. I've really never read anything like it, and it rings deeply true. Michelangelo may or may not have said (almost certainly did not say) that he took a block of marble and chipped away everything that didn't look like "David." Many teachers of writing, myself among them, have counseled that the most important part of revision is cutting. But this different, and I will be thinking about it for quite a while.

A large part of Waldron's goal of shaving that tree down came from Charles Mingus, who caught him trying to play like Bud Powell and gave him a tongue-lashing, telling him never to try to sound like anyone except himself.

But the first clumsy strokes at that tree are always going be taken with borrowed axes, and one of Waldron's first--he had grown up being forced to practice the piano, and hating it--was Coleman Hawkins. It was "Body and Soul" that first made him fall in love with music, and he immediately went out and bought a saxophone:

...An alto. I couldn’t afford a tenor. I got a big, hard reed and an open lay on the mouthpiece so it would sound like a tenor, and I got the music for “Body and Soul” from “Downbeat” and I read it, and for 5 minutes I was Coleman Hawkins!And after that, of course, with an alto:

I was trying to emulate Charlie Parker! But I couldn’t arrive, so I hocked the horn and went back to the piano. Because I found my basis on piano was strong enough at least to enable me to play the changes right.His enforced training on the piano as a child had been classical, which he found too constraining--"I had to do it the same way every time, otherwise I got my knuckles rapped"--nevertheless remained a part of his musical awareness, as did studying composition at Queens College with the eminent German émigré composer Karol Rathhaus. He discussed the importance of the classical influence with Panken:

TP: Did those lessons stay with you in your composition?Waldron is very much of a generation I've discussed a lot. The early beboppers grew up on swing, on Kansas City blues, on the territorial bands, on Basie and Ellington and Lunceford and Erskine Hawkins as well as Goodman and Shaw; Waldron's generation grew up on bebop. But Panken and Waldron make an important point here about this generation that came of age post-World War II, with college and conservatory studies thanks to the G.I. Bill. We know that Charlie Parker listened to everything, and responded strongly to the compositions of Bartok. The fictional Dale Turner, in Round Midnight, speaks for many of his generation when he acknowledges his debt to Debussy.

MW: Definitely.

TP: Your classical background never left you, your sense of harmony and shading…

MW: And form and development, how to develop themes, sure.

TP: I think people aren’t aware of how deeply classical music studies permeated musicians of your generation, who then created a lot of home-grown resolutions and utilizations of it. Can you address that a bit. I guess the G.I. Bill helped a lot of people.

MW: Sure. Well, it had to do with the concepts of Bach. Bach is very basic. The way he moves from V to I, that concept is very instrumental in how the musicians grew. They moved from V to I, and they made it with a flat fifth and putting in stuff like extra notes in the chords and changes like that.

TP: In your circle of friends with Randy Weston and Herbie Nichols, etc., were you talking a lot about classical music and listening to…

MW:Yes, we discussed things like “Rite of Spring” and the sounds and things like that.

The last Waldron session I wrote about was one with Gene Ammons, for which Waldron composed all of the tunes, and I began by imagining a conversation with Bob Weinstock:

And this is probably pretty close to how it went down (including the Friday part: that was Prestige's day in Hackensack)."Mal, you're playing a gig with Gene Ammons this Friday. Come up with some tunes that'll suit him."

"On it."

On many of these dates, like May 2 with Ammons, Waldron was called upon to write the entire session. Here, he only contributes three of eight, the rest being standards. But that's another part of the Waldron story. He was already working as Billie Holiday's accompanist, and he would go on to work with Abbey Lincoln, Jeanne Lee, and other vocalists, so he was spending a lot of time with standards, and that, too, relates over to his work in an instrumental jazz context. As he told Panken:MW: The way the setup was in those days, they’d tell me who was on the set and then they’d tell me to write six or seven compositions for the date. So I had to stay up all night long and write the changes, and next morning I’d come in to Hackensack, N.J., and make the records, then I’d go home and write some more music for the next date.

The way I’d write the tunes, the first important thing was to be able to solo on it. So I’d make my changes first, nice blowable changes that you could solo on beautifully, and then I’d write a tune over the changes.

TP: Write your melody…

MW: Over the changes, yes...my life was consisting of thinking about the melodies in the daytime, writing them at night, and then recording them the next day.

TP: You’d get a phone call, you’d write some music, a bunch of charts or tunes…

MW: Right, and bring them in. We’d run them through maybe for ten minutes, or just talk about them, and then we’d make the record. They were usually all first takes, too.

TP: If you had a date with Gene Ammons and composed “Ammon Joy,” was that based on his…

MW: Yes, on his sound. They’re all connected.

TP: Or writing for Thad Jones or Frank Wess or John Coltrane. In each case you had their sound in mind.

MW: Their sound in mind, sure. That’s the way you write.

[Internalizing the lyrics] really helps me to improvise, because the words give it a completely different atmosphere to improvise on. You can improvise the words alone, instead of just improvising on the changes and the harmony and the melody.In a way, this is exactly what Eddie Jefferson did with "I'm In the Mood For Love."

Waldron takes four songs from what we now call the Golden Age of American song, and the fifth from the era that surrounded him. Sammy Davis Jr., or his spirit, must have been tap dancing through Hackensack in the summer of 1958, because this is the second "Too Close For Comfort" we've had (Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis/Shirley Scott providing the first), along with one "Mr. Wonderful" (per Red Garland).

Kenny Dennis is new to Prestige with this recording. He broke into the jazz scene with junior high classmate Ray Bryant, played with many of the greats, and is still active as the assistant director of the Lab Band at the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts. Among his numerous recording credits is a session with Langston Hughes.

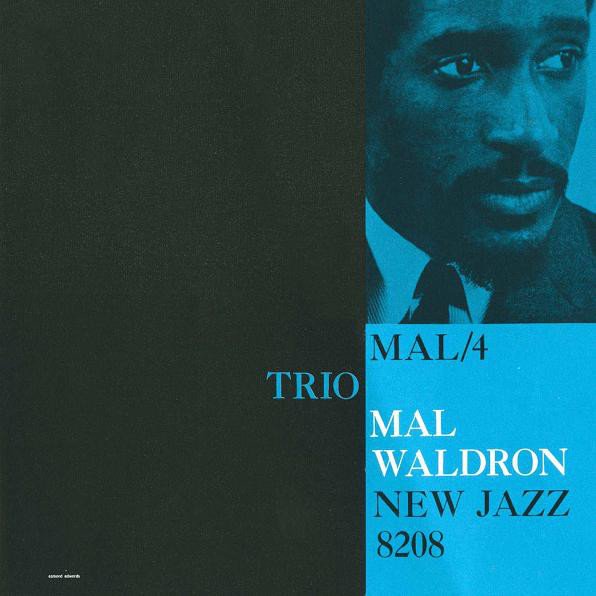

This came out from New Jazz, with Prestige following its pattern of numbering Waldron's albums. This one was Mal/4--Trio.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Tad Richards will strike a nerve with all of us who were privileged to have lived thru the beginnings of bebop, and with those who have since fallen under the spell of this American phenomenon…a one-of-a-kind reference book, that will surely take its place in the history of this music.

--Dave Grusin

An important reference book of all the Prestige recordings during the time period. Furthermore, Each song chosen is a brilliant representation of the artist which leaves the listener free to explore further. The stories behind the making of each track are incredibly informative and give a glimpse deeper into the artists at work.

--Murali Coryell

No comments:

Post a Comment